Ideas into movement

Boost TNI's work

50 years. Hundreds of social struggles. Countless ideas turned into movement.

Support us as we celebrate our 50th anniversary in 2024.

Tunisia is experiencing its worst recorded drought. Though climate change has exacerbated difficulties in the country, water scarcity can be mainly attributed to public policies and economic decisions. These policies have been shaped by deliberate strategies formulated by various foreign entities, which serve the interests of wealthy countries, who continue to exploit and profit from the resources of their former colonial territories through new approaches and means. This article examines the World Bank’s water and sanitation policies in Tunisia and their direct and indirect economic and social implications for the population.

Illustration de: Fourate Chahal El Rekaby

Water is deeply intertwined with human history. No civilisation has ever emerged without access to a reliable water source. Mesopotamia’s name originates in Ancient Greek, and means the 'land between rivers,' referring to the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. The Marib Civilisation emerged around the first dam in human history, with historians attributing the birth and growth of the Sabaean Kingdom to the construction of that dam. Historically speaking, access to water has also been a major catalyst for conflict and war. Water has consistently played a pivotal role in the colonisation of nations, as it served as a compelling motive for seizing control of these regions' water resources and exploiting them to fulfil the interests of the coloniser.

Even as we acknowledge water’s historical significance, the complexities of modern life and increasing demand for water are putting these resources at risk, bringing the world face-to-face with threats to water security in terms of quantity and quality. These challenges have been exacerbated by rising pollution levels, and inadequate sanitation policies have turned some water resources into sources of pollution. Simply put, there are ever increasing threats to the availability of water, especially drinking water, for millions of people worldwide. These issues disproportionately impact so-called poor countries with children, the elderly and women bearing the brunt of these problems.

Global warming has led to reduced precipitation and alterations in the locations and seasonal patterns of rainfall. The United Nations (UN) second Water Conference on 22-24 March 2023 served as an international call to address water issues, particularly in the context of climate change and its impact on rainfall patterns. Tunisia, like most countries, has experienced the impact of these issues. Climate change and the increased demand for water, alongside economic policies, have worsened Tunisia’s water crisis.

Though climate change has exacerbated difficulties in Tunisia, water scarcity can be mainly attributed to public policies and economic decisions. These policies have been shaped by deliberate strategies formulated by various foreign entities, especially international donors. The resulting alignment serves the interests of wealthy countries, who continue to exploit and profit from the resources of their former colonial territories through new approaches and means.

This research paper examines the World Bank’s water and sanitation policies in Tunisia, focusing on the following:

An overview of the water and sanitation situation in Tunisia,

An examination of the World Bank’s involvement in water and sanitation projects in Tunisia,

An assessment of the impact of these policies on water and sanitation, as well as their direct and indirect economic and social implications for the population.

In 1995, the UN categorised Tunisia as one of the 27 countries experiencing water stress. Water stress indicates that the amount of fresh water being extracted from the country’s groundwater aquifers exceeds its replenishment rate. Despite the warning to Tunisian decision-makers at that time, nearly 30 years later little action has been taken to reform the country’s management of water resources, as policies have instead focused only on mobilising and utilising water.

Water resources in Tunisia have been under threat, with an emphasis on directing water toward farming and industry not civilian use, since the early 1970s. This coincided with a period that the country started opening up, becoming more liberal and integrating itself in international markets. Starting then, the Tunisian economy increasingly reoriented itself toward servicing industry and agriculture. This trend continues today and has accelerated the consumption of Tunisian water supplies. In the past decade, climate change has further exacerbated challenges surrounding water supply.

The deterioration of water resources in Tunisia today, both in quantity and in quality, is not solely a result of the country’s geographical location and climate change, as is often suggested. Rather, it has come about through water resource management decisions and policies implemented since the country’s independence in 1956. Squandering these resources in extensive agricultural production for export has reduced Tunisia to a mere supplier for foreign demands, with detrimental consequences for the country’s own water resources and soil.

Tunisia’s approach to managing water resources has proven ineffective, not only because it relied on misguided export-driven development, but also as a result of its limited and narrow perspective on water resources. No regional water policies have been developed that enabled Tunisians to harness the potential of water streams, rivers and deep groundwater aquifers shared with neighbouring countries, like the Intercalary Continental Aquifer.

According to a study published by the Tunisian Institute for Strategic Studies in 2011 on Tunisia’s 2050 water vision, the annual total volume of exploitable freshwater in Tunisia is between 3.8 and 4.8 billion cubic meters (m³).1 According to the same source, this annual water volume is divided as follows:

Surface water: 2 to 2.7 billion m³.

Groundwater: 1.8 to 2.1 billion m³.

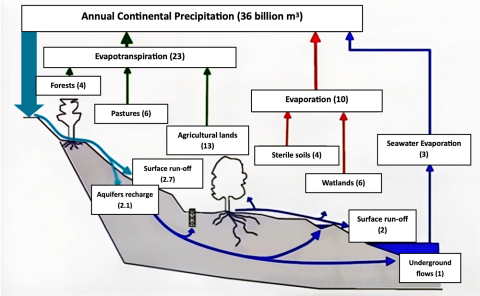

Despite climate change, the average annual rainfall ranges between 30 and 36 billion m³. The probable outcome of the rainfall, given the current public water policies, is as follows:

Houcine Rhili

These figures make it clear that there is still significant potential for harnessing existing surface water supplies more efficiently. A substantial volume of water runoff, especially during heavy precipitation, goes to waste in the sea, salt lakes and humid areas. Based on our analysis, this suggests that Tunisia has the potential to double its surface water supplies to 4.5 billion m³ within the next decade by revising public policies. This would primarily depend on constructing strategically placed dams and securing funding to ensure the efficiency and productivity of these dams.2

Independent of climate change, the potential available surface water in Tunisia has the capacity to fulfil the country’s water requirements and ensure food sovereignty. To achieve this, however, Tunisia must fundamentally change water policies at all three levels: mobilisation, use and investment.

In terms of water use, 77% of water resources are allocated to agricultural activities, 13% for drinking, 8% for industrial purposes and 2% for tourism. Notably, the 77% allocated for agriculture are used to irrigate only 8% of the country’s arable land, i.e., 450,000 hectares only. That means 92% of agricultural land in Tunisia still relies on rainfall for irrigation.3

In many countries, sanitation is directly linked to drinking water, both legally and institutionally. However, in Tunisia this is not necessarily the case as even basic sanitation services are still perceived as a luxury. The institution responsible for sanitation falls under the remit of the Ministry of Environment, not the Ministry of Water. Earlier, the National Office of Sanitation had been part of the Ministry of Equipment and Housing — again, not affiliated with policymakers focused on wider water issues.

The National Office of Sanitation was established by Law No. 73/74 of 3 August 1974, with the mission of managing and treating water used in urban areas, reducing pollution levels and safely discharging wastewater into rivers, salt lakes and the sea. According to Law No.41/93 of 19 April 1993, the National Office of Sanitation was entrusted with safeguarding the water environment at the national level. Half a century since its establishment, the state of wastewater treatment administered by the Office can be summarised in the following table:

Table 1: Available Capacities of the Institution Entrusted with Sanitation

| Number of sanitation stations | 125 |

| Number of municipalities covered | 193 out of 350 |

| Number of clients | 2.157 million |

| Length of sanitation network | 17,848 km |

| Volume of wastewater gathered | 290.8 million m³ |

| Volume of wastewater treated in sanitation stations | 288.5 million m³ |

| Volume of wastewater gathered but not treated | 2.3 million m³ |

Source: Report of the National Office of Sanitation Activities in 2021.

It is important to highlight that the number of clients served by the Office has seen significant growth, increasing from 123,000 in 1975 to 617,000 in 1995 and eventually reached a total of 2,150,000 in 2021. In response to this demand, the number of treatment stations also expanded, growing from five in 1975 to 48 in 1995 and eventually reached a total of 125 by 2021.4

Unfortunately, this growth in the sanitation sector in Tunisia has not been accompanied by a corresponding improvement in water quality. Official reports from the Ministry of Agriculture indicate that the national rate of wastewater reuse remains below 4%. This results in wasting more than 270 million m3 of treated wastewater annually, the equivalent of 50% of the capacity of the Sidi Salem Dam, the country’s largest dam.

Since 1975, sanitation policies in Tunisia have focused on wastewater management in coastal regions visited by tourists, while overlooking the vital basins in the north and northwest, as well as the strategic deep aquifers in the central and the southern parts of the country. These sanitation policies align with the overreaching “coastalisation” trend of development, which prioritizes development efforts to coastal tourism areas, neglecting interior regions, relegating them to being a resource reservoir, and marginalising their populations.

Boat in the desert in Tunisia/Dennis Jarvis/Flickr/CC BY SA 2.0

The World Bank was founded on 27 December 1945, around the same time as the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Its main mission at the time was to help Western European countries and Japan rebuild their industry and infrastructure. Today, the World Bank has 189 member states, including Tunisia.

The World Bank gives loans to states and private companies to finance the implementation of economic projects. Although those loans are not allocated to government budgets, the World Bank, by placing conditions on the loans, still exerts influence on governments and public policies. This influence generally serves the interests of the World Bank’s major stakeholders, primarily the United States of America (US) and other wealthy Western countries.

Since 1956, the World Bank has evolved into a comprehensive group of five financial institutions, each with distinct roles. The most significant ones for Tunisia are the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) and the International Development Association (IDA). The IBRD specialises in providing loans to countries for development projects, while the IDA, founded in 1960, offers loans to developing countries that are less tied to specific projects.

Tunisia’s engagement with the World Bank and the IMF started on 14 April 1958, when it joined both institutions. Tunisia subsequently established its own Central Bank on 19 September 1958, and prepared the first independent budget of the calendar year 1959 after gaining independence from French colonisation. This period also marked the introduction of the national currency, the Tunisian Dinar.

At the time, Tunisia’s President, Habib Bourguiba, failed to persuade the local mercantilist bourgeoisie to invest in an open liberal economy, with competition in the industrial sector particularly limited. Instead, the government adopted a plan devised by the Tunisian General Labour Union, which had been ratified in its 1955 convention under the label of ‘The Cooperatives Project’.5

Given the substantial funding required for such a plan, especially for a newly independent state, the Tunisian government at the time looked for assistance from the US. Bourguiba considered the US as an ally, and during a 1961 visit, secured funds to partially finance his project. Those funds amounted to $238 million. Out of this sum, $47.5 million were provided as a bilateral loan, while the remaining $190.5 million came in the form of grants and aid from the US.6

The Cooperatives Project had a total cost of $620 million dollars over nine years from 1961 to 1969. Out of this total, $238 million were provided by the US and $30 million by the IMF over a three-year period (1964-1966). The remaining $352 million marked the World Bank’s initial financial support to Tunisia at the beginning of their relationship.7

The Cooperatives Programme did not adhere to a socialist path, at least not in terms of its economic and institutional structure. Instead, it supported a form of state capitalism. The World Bank recognised the crucial nature of this phase in building a technocratic and bureaucratic apparatus within Tunisia. It perceived it as a step that could eventually lead the country to allow outside private investment. The programme infiltrated all levels of the Tunisian state, capitalising on its financial, administrative and logistical capacities. Towards the end of 1970 and beginning of 1971, the economy transitioned to a so-called open-door policy, allowing international investors’ increased influence on the domestic economy, in response to perceived shortcomings in the Cooperatives plans.8

IMF activities declined in Tunisia after 1966 and did not regain prominence until 1984 with the introduction of ‘Structural Reform Programme’. Meanwhile, the World Bank continued to provide financial support to the Tunisian government through loans across various economic sectors, including agriculture, water resources, sanitation, education, professional training and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Moreover, the World Bank’s financial and logistical presence grew after the ousting of President Ben Ali on 14 January 2011. This made it Tunisia’s primary creditor in terms of multilateral loans. The World Bank reframed its financial relationship with Tunisia through the establishment of a new credit framework known as the Country Partnership Framework (CPF). This framework spans a five-year period with the possibility of renewal at the end of every term.

According to official figures from the Tunisian Ministry of Finance, which are published every quarter, the country’s external debt through 2019 indicates that the World Bank remains the top multilateral lender with 9,456.9 million dinars ($3 billion in 2023 dollars), constituting 33.56% of multilateral loans.

Since 1959, the World Bank’s loans have been allocated to various sectors, but water resources and sanitation have received a significant portion, accounting for 30.37% of the total funds.9 The lending relationship between Tunisia and the World Bank reached its peak from 2012 to 2016, with loans amounting to $1.15 billion. In addition, the World Bank again began to substantially increase its loans to Tunisia after 2019, within the framework of a programme designed to mitigate fallout from the COVID pandemic. A summary of World Bank loans between 2019 and 2023 is as follows:

Though the World Bank initially suspended Tunisia’s Country Partnership Framework programme for 2023-2027 in response to remarks made by the President about Sub-Saharan migrants that it considered racist, on 22 June 2023 it anyway signed a new Country Partnership Framework agreement with Najla Bouden’s government worth $500 million annually.10

Examining the World Bank’s funding to Tunisia for the period 2020-2026, a total of 2.1 billion euros ($2.2 billion in 2023 dollars) was allocated across various sectors. Apart from the special funds designated to address the social consequences of the Covid 19 pandemic, which were distributed in three instalments totalling 708 million euros ($755 million in 2023 dollars), the remaining projects received 1.4 billion euros ($1.5 billion in 2023 dollars). Notably, within this allocation, projects related to water (including efforts to improve irrigated agriculture, respond to natural disasters and enhance food security) and collaborations between the public and private sectors in sanitation were granted 435 million euros ($464 million in 2023 dollars). This constitutes 30.2% of the total funds mentioned above.

These figures raise several pertinent questions: What makes water and sanitation so significant for the World Bank Group? What are the Bank’s policies in these two sectors? And how have these policies influenced the efficiency of the water and sanitation sectors, which are services vital to the wellbeing of citizens?

As a response to the vital importance of water resources, Tunisia developed several 10-year national plans. The early national water plans, implemented between 1960 and 1990, focused on harnessing available water resources and directing it toward agricultural production. There were initiatives for water distribution across the northern, central and southern regions of the country.11 These projects required substantial funding and were geared towards agricultural production, with a portion of the output then designated for export to generate hard currency. In essence, these projects aimed to export the surplus value of the local economy to wealthier nations.

As an example, according to various published studies, the World Bank provided funding of around $352 million between 1961 and 1969.12 This support was instrumental in the implementation of integrated agricultural cooperatives, which played a pivotal role in establishing a state capitalist system. Several dams were built during this period, with either full or partial funding from the World Bank. Notable examples include Lakhmess dam in 1966, the Kasseb dam in Beja in 1969, the Nebhana dam in Kairouan in 1965 and the Sidi Chiba and El Massri dams in Nabeul in 1963 and 1968, respectively.13 These dams served as the primary water source for the new irrigated areas and industrial projects linked to agricultural production within the framework of integrated agriculture at the time.

Throughout the 1970s, the World Bank continued to encourage an exported-oriented economic model in Tunisia by financing water infrastructure projects. These projects included the building of new dams and water conduits to the Cape Bon, the coast and the town of Sfax, alongside the establishment of both public and private irrigated zones. Altogether, the total loan allocation for the water and sanitation sectors since 1961 is 4,383.33 million dinars ($1.4 billion in today’s dollars). Notably, 80% of these funds were allocated for water, with the remaining 20% directed towards sanitation.14 Projects financed by the World Bank have remained integral to the implementation of Tunisia’s national water policies.

In assessing the World Bank’s funding in Tunisia’s water sector, attention needs to be directed to the 1961-1969 period mentioned above, during which it provided $352 million dollars (an average of $39 million per year), with at least 30% dedicated to water-related projects. This proportion equates to $13 million per year at the time, a substantial sum compared to current allocations.

After January 14, 2011, the World Bank extended a line of credit to Tunisia to facilitate the democratic transition post-revolution, covering the period from 2012 to 2016. This credit line amounted to $1.15 billion dollars, allocated across various sectors, as illustrated in the graph below:

A full $210 million of this credit line went to fund projects of water and sanitation between 2012 and 2016, with a $100 million dedicated to water projects and $110 million for sanitation. The World Bank, via its subsidiary IBRD, continued to support the areas of drinking water and irrigation from 2017 to 2019, with an annual average of $23.7 million. This amount is notably lower compared to the Bank’s funding levels during the 1960s and 1970s. Regarding drinking water, the National Company for the Exploitation and Distribution of Waters (SONEDE) obtained financing from the World Bank to execute one of its most significant projects, namely “Delivery of Drinking Water to the Urban Centres and the Greater Tunis Area” initiative. The World Bank completely funded the project and its additional components between 2005 and 2015. The initial cost was $59 million, with a cost overrun of $20 million, resulting in a total cost of $79 million.15

Over the same timeframe, the World Bank facilitated meetings between SONEDE and several international donors, with the International Finance Corporation (IFC) acting as a guarantor for creditors. The World Bank, represented by the IFC, provided a grant of 7 million dinars ($2.27 million in 2023 dollars) on August 7, 2023, to the Gafsa Phosphate Company. This grant was allocated to conduct a study on a 'Hydraulic Transportation’ project for phosphate, which sought to transport phosphate from production to processing sites. This is potentially concerning because the grant’s official purpose is to support the company in exploring scenarios and techniques to pump phosphate from the mining basin utilising water that would come from a desalination plant that is being planned in the coastal area of Skhira, with an estimated cost of 1100 million dinars ($349 million in 2023 dollars).16

This is sufficient to prompt suspicions that the World Bank aspires to infiltrate the phosphate production network via this project by establishing partnerships between the Gafsa Phosphate Company and foreign investors who will partake in both the project implementation and the exploitation. If true, this initiative could gradually pave the way for the privatisation of the vital phosphate sector, with the water crisis in the mining basin serving as justification.

The World Bank provision of funding or financial guarantees to the public institution responsible for drinking water in Tunisia marks a notable shift in its policy orientation and increased involvement in the water sector. Collaborating with other donors like the German Development Bank KFW, the World Bank has begun promoting two key concepts: enhancing the governance of the drinking water management institution and advocating for realistic pricing of drinking water. This approach represents a clear step toward potential future privatisation of the drinking water supply.

The sanitation sector in Tunisia has undergone several phases of change, beginning with the establishment of the National Office of Sanitation in 1974 to collect and treat wastewater in urban areas. In 1993, this office was further tasked with protecting the overall water environment, signifying a notable shift in its mission. This shift can be attributed to two main factors:

The incorporation of the National Office of Sanitation into the Ministry of Environment, which gave it an environmental dimension. This move enabled the office to access substantial funding, particularly after the Earth Summit in Rio in 1992.

The involvement of the World Bank as a key donor for sanitation projects.

The World Bank funded the development of a major wastewater treatment plant. This development and expansion of the Chotrana Station for Treating wastewater north of the Tunisian capital (1996-1999), thus increased its treatment capacity to reach 40,000 m3 per day. The World Bank supported this project with a loan of around $32 million at the time. It also funded the project of the Al Attar wastewater treatment plant west of the capital, the largest treatment station in the country with a capacity of 60,000 m3. The project cost was around $104 million in 2005. The station connected about 600,000 residents residing west of Tunis to the public sanitation network.17

Moreover, the World Bank financed the construction of wastewater treatment plant in Sfax and smaller facilities in Sousse, Monastir, Kairouan and Tataouine. It also funded a marine channel project designed to transport treated wastewater from the plant in Sousse, along with supporting several studies aimed at enhancing sanitation services and the agricultural use of treated water.18

Since 1995, the World Bank has been providing technical and logistical support to the National Office of Sanitation. This support has led to the privatisation of sanitation services, previously referred to as a ‘spin-off’, which commenced in 1997 within the framework of restructuring the National Office of Sanitation. Starting with the launch of the national programme of waste management in 1996, the World Bank aimed to create an organic link between the sanitation and solid waste management sectors to facilitate private sector involvement, based on so-called public-private partnerships.

To create the impression that this policy began as a Tunisian initiative, the World Bank established a network of local experts tasked with producing reports and publishing studies advocating the advantages of privatising sanitation and waste management. Senior positions within public administrations promoted this strategy using varied labels and slogans, thereby advocating the World Bank's directives.19

As a result of this pressure from the World Bank and the influence of the reports produced by local experts, Tunisia made amendments to its Water Code, originally issued by Law No. 75-16 of 31 March 1975. These changes aimed to introduce privatisation into the water sector, even if only as a temporary measure, as outlined in Law No. 01-116 of 26 November 2001. Article 86 was revised to reaffirm that water is a national resource that ‘must be developed, protected and used in a sustainable manner.’20 Additionally, Article 88 was amended to explicitly permit ‘the production and utilisation of non-conventional water resources that meet specific conditions for private consumption or use on behalf of others within a defined industrial or tourist area.’

The wastewater treatment plant in Tataouine, funded by the World Bank, marked a significant milestone as it became the first facility to be fully entrusted to a private company in 2003. This signalled that that the private sector had the potential to become involved in all primary and secondary activities undertaken by public institutions through concession agreements, with the French company SEGOR Industries receiving the inaugural concession.21

The transfer of exploitation rights for treatment stations to the private sector continued in several cities until 2010. However, smaller treatment plants did not attract private companies, nor were they of significant interest to the World Bank, as they were not seen as attractive targets for private investment.

In May 2023, after the enactment of Law No. 15-49 of 27 November 2015, regarding public-private partnerships, the World Bank achieved another significant milestone. It established the first partnership between the public sector, represented by the National Office of Sanitation, and the international private sector, represented by the French company, Suez, known for its extensive involvement in water and sanitation projects across Africa. This partnership was facilitated through a $126 million loan.22

The project involves developing and operating 15 wastewater treatment plants in Tunis and Ariana in the north of the country, as well as in Sfax, Gabes, Medenine and Tataouine in the southeast. It aims to enhance the treatment of wastewater by incorporating tertiary treatment process to ensure the treated water meets agricultural usage standards.

The reason the World Bank did not directly extend this loan to the public institution for implementing measures to improve water quality to meet industrial and agricultural standards is quite clear. The World Bank’s policies are not geared towards enhancing the capacities of public institutions. Rather, they are focused on penetrating the public sector on behalf of the private sector, and especially on behalf of international capital. The private sector’s successful two-decade long involvement in the sanitation sector paved the way for the World Bank to embark on a large ‘public-private partnership’ in Tunisia.

Dennis Jarvis/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

The World Bank, along with other donors, typically focuses funding on major infrastructure and the construction of central water treatment or wastewater facilities rather than directly funding citizen services. Public services companies are responsible for essential aspects of water and sanitation, such as connecting homes to water and sanitation networks. As a result, the loans are guided by economic return indicators or the potential for the private sector to exploit the established infrastructure and facilities in the future, often in the form of a concession or partnership with the public sector. The table below provides a summary of projects funded with external loans in water and sanitation sectors between 2017 and 2019:

Table 2. Water and sanitation projects funded by external donors from 2017 to 2019

| Projects | Funding Cost (in millions of dollars) | Percentage of funding |

|---|---|---|

| Major conduits of water transportation | 128.9 | 28.6% |

| Sanitation channel main pipes | 113.6 | 25.22% |

| Policies and administrative management of water | 183.3 | 40.7% |

| Construction of water basins | 13.7 | 3.04% |

| Conduits of water distribution | 8.3 | 1.84% |

| Connecting homes to sanitation networks | 0.2 | 0.004% |

| Protection of water resources | 1.9 | 0.04% |

| Training and education in water and sanitation | 0.4 | 0.008% |

| Total | 450.3 | 100% |

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 23

This table indicates that between 2017 and 2019, 93.89% of multilateral external funds were allocated to projects related to treatment stations, water transportation to irrigated areas, wastewater transportation and water management policies. Conversely, just 6% of the total funding was designated for projects aimed at improving citizen access to drinking water and sanitation networks, protecting water basins and resources, or providing training and education in the water and sanitation sectors.

These kinds of funding allocations have consequences. Public institutions also face structural problems like corruption and poor decision-making. Moreover, private investors often neglect the maintenance and replacement of drinking water distribution pipelines, directly impacting water quality. This situation mean water distribution pipes are often left in place in excess of 20 years and even 40 years in some regions. The lifespan of these pipes depends on factors like salinity, carbonates’ quantity, and temperature, with higher levels of these factors increasing the risk of future water quality issues and losses from leaks and damage.24 Institutions responsible for providing essential drinking water and sanitation services often lack resources, shifting the financial burden to citizens. This situation was confirmed by a 2018 World Bank report on drinking water and wastewater in Tunisia, revealing that 94% sanitation services cost is covered for by the families through sanitation fees on their water bill, while the government contributes just 6% of the total cost.25

As for drinking water, Tunisian households bear 75% of the overall expense. Tunisian families spent more than $671 million in 2015 on drinking water and sanitation services, equivalent to 1.5% of the government total expenditure for that year. This translates to a yearly average per capita expenditure of $66 in urban areas and $38 in rural areas.

While individual spending on drinking water and sanitation in Tunisia has risen, public investment in these sectors amounted to just $17 per capita for 2017. This figure is notably lower than that of comparable countries like Jordan ($55) and Lebanon ($102).26 The comparison with Jordan and Lebanon is relevant because of the similarities in public policies on water and sanitation among these three countries.

All of the above falls within the broader framework of the World Bank’s policies, impacting project selection and directing focus to sectors that are attractive to both local and international private investors. However, the consequences of these policies, directives and mandates since 1959 have been severe, and occasionally disastrous, affecting productive sectors, water resources and leading to direct social and economic hardships for citizens in their daily lives. The following points summarise these repercussions.

The dominance of a new generation of investors, unfamiliar with agriculture and land issues but empowered by their positions and access to credit, has led to investments in irrigated areas. As a result, small-scale farmers and social production networks that produce grains, poultry, red meat, and dairy were overlooked.

Small farmers abandoned their regions and agricultural work in pursuit of more profitable opportunities, especially during a period of extreme internal migration between the mid-1970s and 1980s.30

As a result, the agriculture sector economic input fell to 8% of the GDP in 2022, down from 17% in the early 1990s. Similarly, its role in employment decreased from 23% in the early 1990s to just 12% in 2022.31

This approach inevitably led to the decline in the production of essential items like vegetables, fruit and animal feed. Only products intended for export have consistent access to water, deepening the country’s dependence on the international market, especially for grain and animal feed. The continued difficulties in securing staples such as bread, vegetable oil and sugar confirm the problem.

As for drinking water, prices have increased threefold in three consecutive years (2020, 2021, and 2022). The public company raised rates from 0.2 dinars ($0.06 in 2023 dollars) per m3 to 0.665 dinars ($0.21 in 2023 dollars) in three years for the most common consumption range, 20-40 m3 per trimester.

The deterioration of drinking water quality is a result of outdated networks and insufficient public investment aimed at improvement. Increased dam water salinity due to the accumulating hard residues has exacerbated the issue. This had led to a significant shift, with Tunisians ranking fourth globally in per capita bottled water consumption, as reported by the National Institute of Consumption in 2021.

Claiming a lack of external funds and public investment, the National Office of Sanitation is forced to reduce its wastewater management efforts in small municipalities in inland areas. It now collects wastewater on a limited scale and discharges it untreated into the natural environment. This has aggravated pollution in these regions and adversely affected living conditions, leading to issues like mosquitoes and foul odours in discharge areas near rivers close to cities. This threatens the cleanliness of surface water tables and poses potential health risks, including skin diseases.

The spinoffs and private concessions implemented in Tunisia’s sanitation since 1997 failed to enhance wastewater treatment technologies or water quality. Instead, they primarily benefited the private sector and foreign capital, allowing them to profit without making significant improvements to the wastewater treatment stations they took over from public institutions.

McKay Savage/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

Historically, Tunisians have coped with water scarcity. But the water crisis in Tunisia is fundamentally structural, tied to shortcomings in public policies and economic decisions. Paradoxically, water sanitation is still considered a luxury, with the National Office of Sanitation covering only 193 out of 350 areas nationally. Those places that are covered are primarily located in coastal and tourist regions. This study examined World Bank funding for Tunisian water and sanitation projects since the 1960s, evaluating their bias towards capitalist approaches that diminish the state's role in favour of the private sector. The evidence presented leads to the following conclusions regarding the objectives of the World Bank's policies in these sectors:

Utilising local water resources to produce agricultural and industrial goods for export.

Encouraging both local and foreign investors to capitalise on the irrigated zones to cater to foreign demands.

Withholding loans from projects aimed at providing direct services to citizens such as drinking water and irrigation for small-scale farmers.

Focusing funds on major infrastructure within the water and sanitation sectors, with the idea that they may become subject to privatisation in the future.

Channelling technical and logistical support, as well as sectoral studies, towards the privatisation of water and sanitation services.

These policies have had significant impacts on people’s socio-economic status, both directly or indirectly, as they mark the state’s withdrawal of its essential social role in the water and sanitation sectors. These consequences have been severe on multiple levels, contributing to:

Despite the World Bank’s efforts to influence Tunisia through loans and policies, leading to a partial privatisation of sanitation services in May 2023, it has not succeeded to privatise the overall water sector, including drinking water. This precarious achievement is the fruit of the significant work done by civil society, progressive organisations and democratic parties, particularly in the past decade.