Ideas into movement

Boost TNI's work

50 years. Hundreds of social struggles. Countless ideas turned into movement.

Support us as we celebrate our 50th anniversary in 2024.

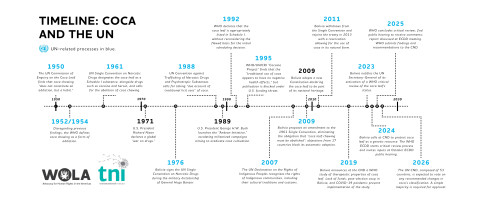

The decades-long ban of the coca leaf in UN drug treaties and the reform opportunity offered by the recent World Health Organization (WHO) review process featured prominently at the 67th session of the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) in Vienna, March 14-22, 2024. The first issue of the Coca Chronicles discussed the current classification of the coca leaf in Schedule I of the 1961 UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (or its effective ban) and Bolivia’s initiation of the WHO critical review process. This second episode of the Coca Chronicles highlights three developments during the recent CND session: (1) support for the coca review from the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights; (2) Bolivia’s call to protect the coca leaf as a genetic resource; and (3) an update on the WHO’s preparations for the review.

Illustration by Anđela Janković

“The natural coca leaf is like an emblem that protects the identity of the Andean-Amazonian Ancestral Peoples.”

The main focus of Choquehuanca’s speech was on the need for international legal protection of the coca leaf as a genetic resource and heritage of the Andean-Amazonian Indigenous Peoples. He pointed at two mechanisms that could be explored for that purpose: the Nagoya Protocol of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the upcoming legal instrument on traditional knowledge associated with genetic resources negotiated under the auspices of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO).

The Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits contains provisions on the rights of Indigenous Peoples to sustainably use and benefit from the utilization of their genetic resources, including plant species. An example is the Rooibos agreement with South Africa’s KhoiSan people in which “the industry behind the herbal tea rooibos has agreed to pay a percentage of the money that is made to the indigenous people who used the plant before production was industrialised.” Gabon has been trying to apply the Nagoya rules to protect its native psychedelic plant iboga; the proposed agreement could “put an end to the illegal trade in Gabon’s ‘Sacred Wood’ and finally be able to allow traditional communities to also benefit equitably from the economic benefits of this ancestral national heritage.”

In the case of the coca leaf, multiple Indigenous Peoples across the Andean-Amazonian region share long-standing traditional uses and knowledge. In that context, Choquehuanca drew attention to the Protocol’s Article 10 which provides the option of “a global multilateral benefit-sharing mechanism to address the fair and equitable sharing of benefits derived from the utilization of genetic resources and traditional knowledge associated with genetic resources that occur in transboundary situations”, as is the case with coca leaf. At the Conference of the Parties of the CBD and its Nagoya Protocol scheduled for October 2024 in Colombia, according to Choquehuanca, “we could discuss the usefulness of a multilateral transboundary mechanism to protect the seal of the genetic information of the coca leaf.”5 [SPA 2] The Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement on Appellations of Origin and Geographical Indications, protecting products that have a particularly strong link with their place of origin, also offers the possibility of a joint application, under Article 5(4), in case of a trans-border geographical area of origin.

Meanwhile, also under WIPO auspices, a Diplomatic Conference on Genetic Resources and Associated Traditional Knowledge is scheduled to take place from May 13-14, 2024, in Geneva. The conference will aim to adopt a new legal instrument to enhance the protection of Indigenous Rights within the current intellectual property regime. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, in Article 31, provides that Indigenous Peoples have the right to control and protect the intellectual property over their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions. The current intellectual property regime, however, does not recognize those rights, and in practice Indigenous Peoples often face exploitation, misuse, misappropriation and theft of their genetic resources and traditional knowledge. A WIPO intergovernmental committee has been meeting for over two decades to address those gaps in the regime, and twice an Indigenous expert workshop has been convened to contribute to the process. The latest one, in February 2023, provides detailed comments on the draft text and expresses hope that “this instrument has a chance to redress the discriminatory nature of the current intellectual property system and establish mechanisms to recognize rights of Indigenous Peoples over their intellectual property at the international level.”6 The Indigenous experts also drew attention to the need to cooperate on transboundary matters, suggesting to set up a regional Indigenous body to effectively deal with genetic resources, traditional knowledge and cultural expressions that are spread over more than one State.

Addressing the transboundary challenges of the Nagoya Protocol and the WIPO negotiations, Choquehuanca has proposed convening a workshop of experts from the Indigenous communities cultivating coca leaf across the Andean-Amazonian region. A mechanism to protect the coca leaf as a genetic resource associated with traditional uses and knowledge has a double objective, said Choquehuanca:

“The hoped-for scenario that the critical review process conducted by the WHO results in liberating the coca leaf from Schedule I, would open the possibility of a legal international market for coca products in their natural or industrialised form. We want to ensure that a possible opening cannot be misused by foreign commercial companies, prevent the approval of patents related to the coca leaf without prior informed consent, and ensure that a large part of the revenues from a future legal market for natural coca leaf products contributes to the development of the Andean-Amazonian cross-border Indigenous peoples. At the same time, having a protection mechanism in place using the aforementioned international instruments, reinforced by national legislation and regional agreements, would help prevent the proliferation of cultivation and production of coca leaf products without adequate control in the event of the opening of international markets.”7 [SPA 3]

In that regard, valuable lessons can be drawn from Peruvian efforts to protect the maca plant against biopiracy and patenting by foreign companies. Maca roots have also been used by Andean Indigenous Peoples for thousands of years for nutritional and medicinal purposes. A booming international market for maca as a ‘superfood’ and natural medicine led to maca cultivation in China and U.S. companies acquiring patents over certain maca extracts. There have not been attempts by Indigenous groups to claim patent ownership of maca: “They avoid designating which groups have the right to the plant by keeping it in the realm of communal knowledge and cultural property.”8 Instead, Peru responded by strengthening domestic legislation and appealing to international protective mechanisms to revoke foreign patents.

In conclusion, Choquehuanca argued in Vienna that “the truth about the coca leaf, as a natural resource and not a drug, is gradually emerging in the collective consciousness” and that the “the full legalisation of the production and consumption of the coca leaf in its natural state would provide great benefits to humanity and great opportunities for industrialisation and commercialisation for the cross-border Indigenous Peoples of Bolivia, Peru, Colombia and Ecuador.” [SPA 4]

The globalization of uses of psychoactive plants from their original traditional niches to new cultural contexts comes with many challenges, and lessons can be learned from experiences with ayahuasca or kratom, for example. In the case of coca a process of diversification has taken place over the centuries as the use of the plant spread out of the original Indigenous areas into the northern Andes, the western Amazon basin and southwards into Chile and Argentina. Novel forms of consumption have continued to emerge in urban settings within the region, as well as abroad, following Andean migration patterns and through small-scale internet sales. As mentioned in the supporting dossier Bolivia submitted with the review notification, it is no longer possible today “to consider ancestral customs as the sole, properly valid point of reference, and in the process disqualify the wide range of present-day developments as somehow less legitimate”.9 [SPA 5] Still, to prevent corporate capture of international coca markets and to ensure that benefits will support Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the region, it will be important to use the Nagoya Protocol and WIPO mechanisms for the protection of cultural heritage, genetic resources, traditional knowledge and geographical indications.

The ECDD secretariat, present at the CND session in Vienna, provided some updates on the preparations for the coca review process. A team of authors from various scientific disciplines selected by the secretariat will start working on the critical review report in May. Given the complexity of this particular review, the report will not be finished in time for consideration at the ECDD meeting scheduled to take place October 14-18 this year. However, the public hearing on the first day of that meeting will be used as an opportunity for Indigenous Peoples, civil society and academia to provide inputs for the coca leaf review that can be taken into account in constructing the critical review report. Details about registration for that online information session and some guidance notes for those who wish to submit interventions will be available in September. After the October 2024 meeting and following usual practice, the WHO will send around a questionnaire to Member States to submit relevant information they want to be considered by the ECDD. A second public hearing will then be held in October 2025 once the critical review report is available. For the timeline of the process, this means that the outcomes of the WHO coca review will not be presented until the end of 2025. As a result, the earliest an eventual CND vote on a WHO recommendation to change the current scheduling of the coca leaf could take place would be the reconvened 68th CND session in December 2025 or―more likely―the 69th CND session in March 2026.

The ECDD secretariat had also requested the opinion of the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) as to whether the WHO could undertake a review of the coca leaf alone, without including intermediate products created in the process of manufacturing cocaine. The question arose because the annex of the Yellow List of Narcotic Drugs Under International Control (maintained by the INCB) includes ‘coca base’ as a synonym for ‘coca leaf’. ‘Coca base’ (more commonly referred to as ‘cocaine base’) is an intermediate product in the process of cocaine production, after the initial extraction of ‘coca paste’ which appears in the same list as a synonym for ‘cocaine’. In the supporting dossier, Bolivia pointed out the inconsistency and argued that it required a correction. In a bilateral meeting between the Bolivian delegation and the INCB that took place during the CND, INCB President Jallal Toufiq explained that the Board had discussed the matter and acknowledged that listing ‘coca base’ as a synonym for ‘coca leaf’ was a mistake and that the INCB will correct it accordingly in the next updated edition of the Yellow List. The INCB has notified the WHO of their conclusion, clearing the way for a separate review of the coca leaf.

It is still unclear at this stage to what extent the WHO will be able to accommodate the appeals made by Bolivia, the High Commissioner on Human Rights and the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues to secure meaningful participation of Indigenous Peoples and incorporate knowledge of Traditional Medicine in the review process. Possibilities for doing so could include involving the WHO Global Traditional Medicine Centre; liaising with the OHCHR Indigenous Peoples and Minorities Section, the Expert Mechanism and the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous People; requesting an opinion from the Permanent Forum; and facilitating participation of Indigenous experts in a special ECDD meeting to discuss the critical review report.

This review holds significant potential to revise drug policies for the better, with corresponding impact on the lives, livelihoods and ancestral traditions of Indigenous Peoples the world over.

The coca issue and Indigenous Rights more broadly came up in several other statements and side events, a promising sign that these issues are getting more attention in global drug policy debates. Attempts to introduce stronger language in defence of Indigenous Rights in a resolution on alternative development triggered hours of negotiation in the Committee of the Whole, but ended in a weak compromise with many caveats:

[Encouraging] Member States, including within their efforts to implement the United Nations Guiding Principles on Alternative Development to engage, where appropriate, Indigenous Peoples and local communities affected by illicit drug crop cultivation and other illicit drug-related activities in the development and implementation, including, within the decision making process, in accordance with domestic and applicable international law, of policies and actions aimed at promoting sustainable alternative development, taking into account their culture, knowledge and traditions

At a side event about aligning drug policy with Indigenous knowledge and practice, Scott Wilson, from the Aboriginal Drug & Alcohol Council in Australia and actively involved in the formation of the International Indigenous Drug Policy Alliance, called on the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) to establish an Indigenous Expert Advisory Committee and proposed that the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues develop a position on drug policy. A side event on Psychoactive Plant Practices and Cultural Rights discussed the relevance of the coca review process and the defence of coca leaf traditions in Spanish courts. And on the last day of the CND session, a virtual Consultation on the Legal Status of the Coca Leaf was held to discuss the coca review process.

Colombia played a very active role on many fronts at this CND session, including the critical leadership of the Colombian Ambassador in Vienna, Laura Gil, in the negotiations on the outcome document and resolutions, which led to a historic ‘Breaking of the Vienna Consensus’. Colombian President Gustavo Petro said in his video statement at the opening session that “we wasted money, we turned indigenous and Afro-descendants into our enemies, and we sacrificed our development for a war that others wanted”. “Coca leaves are part of our history”, he added, and “we will give oxygen to the peasants who grow coca leaves” while continuing the fight against criminal organizations profiting from illicit cocaine trafficking.

A representative of the International Indigenous Drug Policy Alliance, Diego Andrés Lugo-Vivas from Cauca, Colombia, was one of the few civil society speakers at the high-level segment. He talked about the dramatic level of violence against human rights defenders in Colombia, where since 2016 more than 1,200 social leaders have been killed, including many peasant and indigenous leaders. “Coca regulation”, he said, “must pursue the decriminalization of the most vulnerable groups (producer families, on the one hand, and consumers on the other).” At a side event on Licit Uses of Coca Leaf, Andrés López, former director of the National Narcotics Fund at the Colombian Health Ministry, explained the legal treaty exemptions for industrial uses of coca; and Felipe Tascón, head of the Colombian alternative development programme (PNIS), called for the “necessary removal of coca from the prohibition index”. [SPA 6]

Overall, the coca leafcritical review process was visibly present at the March 2024 CND, and received important support from various actors within the UN system as well as civil society. Important questions remain as to how and whether the WHO review now underway can encompass the multiple dimensions of the coca leaf’s status within the UN drug treaty system. But the level of engagement at the recent CND session offered , a promising sign for the future.

Upcoming events in 2024:

April 15-26, New York, UN: UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues 23rd session

April 27-28, San Francisco, U.S.: Chacruna conference Psychedelic Culture 2024, with a panel on the coca leaf

May 13-24, Geneva, UN: Diplomatic Conference on Genetic Resources and Associated Traditional Knowledge

May 15-19, Marrakech, Morocco: 18th Congress of the International Society of Ethnobiology, Biodiversity & Cultural Landscapes: Decolonial, Indigenous and Local Perspectives, with a panel on the coca leaf

October 14-18, Geneva, UN: 47th meeting of the WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence, including a public hearing on the coca leaf review process

October 21-1 November, Cali, Colombia: UN Convention on Biological Diversity Conference of thee Parties (COP-16)including COP-5 of the Nagoya Protocol